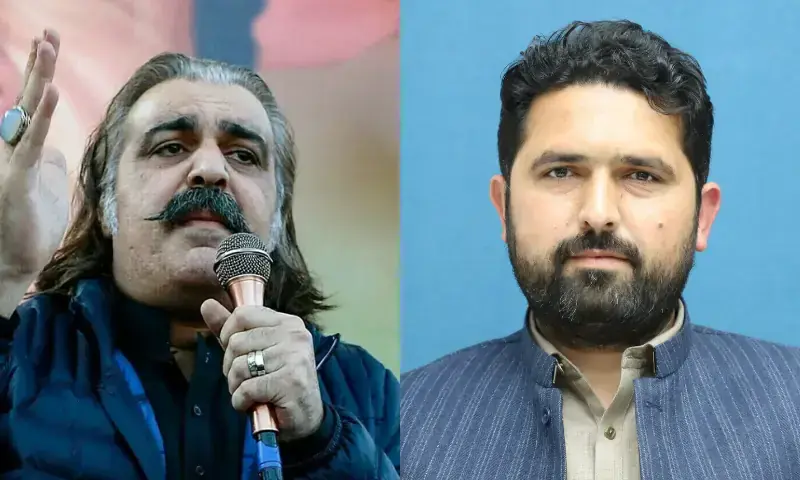

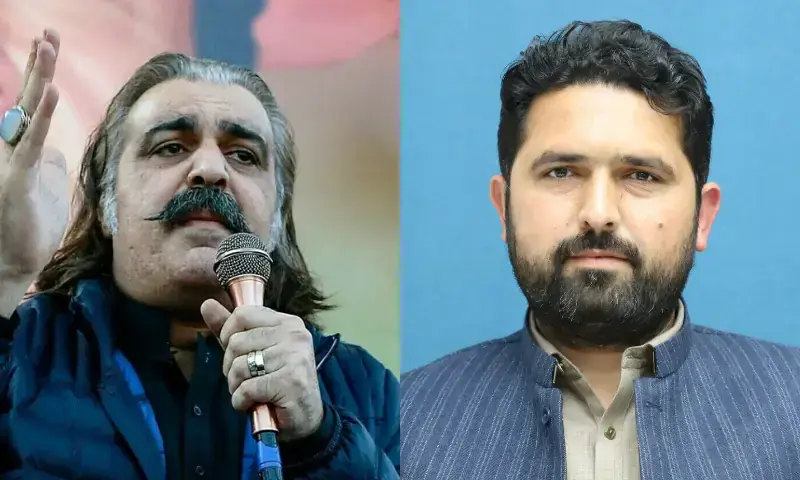

In a day of high political drama at the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Assembly, PTI’s Sohail Afridi was elected the province’s new chief minister. However, his victory unfolded amid walkouts, protests, and a deepening constitutional crisis over whether the outgoing CM, Ali Amin Gandapur, had even truly vacated his seat.

As chants of “Sohail Afridi zindabad” echoed through the assembly hall, the opposition staged a walkout, declaring the entire process “unconstitutional.” Speaker Babar Saleem Swati, however, pressed ahead and ruled it lawful under Article 130, declaring Afridi’s election valid even as questions swirled over Gandapur’s disputed resignation, returned by Governor Faisal Karim Kundi for having “disparate signatures.”

The episode has set off a flurry of debate: can a new chief minister be elected when the previous one still holds office? Lawyers have since weighed in, dissecting whether the assembly’s actions uphold or undermine the constitutional process.

An attempt to thwart the will of the many

“The opposition walkout means nothing; just as the governor pretending to become Sherlock Holmes about signatures matching is irrelevant,” remarked lawyer Abdul Moiz Jaferii. “The CM resigned — his resignation is effective immediately. The house has chosen a new leader.”

In his view, the matter is straightforward: there is only one chief minister in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, “the one the majority of the members of the provincial assembly voted for today.” Any attempt to halt that process, he argued, “is a sorry and desperate game of the few attempting to thwart the will of the many.”

As Jaferii pointed out, political actors often justify such manoeuvres by citing past precedent, but that, too, fails the constitutional test. “The excuse we are presented with is that it has happened before too,” he said. “No one even bothers to deny that it is as wrong now as it was then and that it is the constitutional order that pays the price.”

While he argued that the assembly’s vote is decisive and the governor’s signature drama irrelevant, some lawyers see a clear breach of constitutional procedure.

A constitutional anomaly unfolds

Lawyer Mirza Moiz Baig termed the situation “a constitutional anomaly,” questioning both the governor’s delay and the speaker’s haste. “While the governor’s refusal to accept the chief minister’s resignation is inexplicable given that the former has publicly confirmed the same,” Baig noted, “the speaker’s decision to call a session to elect a new chief minister before the acceptance of CM Gandapur’s resignation is a constitutional anomaly.”

Baig pointed out that the Constitution provides a clear timeline in certain situations, such as when a chief minister dissolves the assembly, the decision takes effect within 48 hours even if the governor does not act. “Interestingly, no similar provision exists in the event that the chief minister resigns,” he said.

In Baig’s assessment, though, the speaker may have overstepped. “While the Assembly may have voted CM Gandapur out through a vote of no confidence or while the courts’ jurisdiction may have been invoked against the governor’s procrastination, the KP speaker’s decision is untenable.”

History has little patience for delays

“While there can’t be two CMs at once, the central principle is this: ceremonial bottlenecks cannot defeat the Assembly’s will,” said lawyer Ahmad Maudood Ausaf. “If a governor frustrates and tries to delay that process beyond reasonable verification, as has been the case here, by that point, a letter, another letter, a speech, and a tweet should have sufficed.”

Ausaf added that “any court would view it as unconstitutional, especially since the courts — Punjab, Peshawar, Islamabad — have intervened before to prevent such artificial, managed, and unconstitutional manoeuvring.” In his view, a mere opposition walkout cannot invalidate a process where quorum is met and the assembly’s will is clear. “History, after all, has little patience for ceremonial delays,” he said. “It records only those who stood firm when others hid behind procedure.”

A risk of constitutional overlap

Lawyer Ayman Zafar argued that while the Constitution envisions “a single CM as the executive head of a province, the real dispute lies in interpretation.“

“The key question is whether the outgoing CM has been constitutionally removed before proceeding to elect a successor,” she said. “While the Constitution does not require the governor’s formal acceptance of a CM’s resignation, Article 133 allows the governor to request the CM to continue until a new one is appointed.”

She cautioned that the governor’s inaction may, in effect, trigger Article 133 — allowing the incumbent to remain in office until a successor is chosen through a settled process. “Proceeding with the election of a new CM before the incumbent’s position is conclusively settled risks creating a constitutional overlap,” Zafar noted. “Even if quorum is technically met, the absence of procedural clarity may undermine the legitimacy of the outcome and invite judicial scrutiny.”

But to others, the legality of Afridi’s election is beyond dispute.

The democratic and constitutional process stands complete

“There is no legal or constitutional provision requiring the governor of KP’s assent for the former Chief Minister’s resignation to become effective,” asserted lawyer Zainab Shahid. “As per Article 130(8), the only requirement is that the CM resigns ‘by writing under his hand addressed to the governor’. The former CM has done so twice.”

Shahid termed the governor’s repeated rejection of Gandapur’s letters — first denying receipt, then objecting to mismatched signatures — “illegal attempts to delay the appointment of an ‘undesirable’ new Chief Ministerial nominee and obstruct a democratic vote.”

“Once the former CM has resigned through multiple letters and publicly declared his resignation,” she said, “there is no bar on the KP Assembly from convening to elect a new CM.”

With Afridi securing 90 out of 145 votes, Shahid argued that the democratic and constitutional process stands complete. “All state institutions and actors should accept this outcome as the rightful will of the people of KP,” she added, “instead of continuing to make a mockery of the Constitution.”

For now, though, KP remains in uncharted territory — a province with, at least on paper, two men claiming the same chair, and a constitutional fog thick enough to blur even the clearest lines of authority.